Teens/adults - Lesson 1: Can I draw if i think, “I can’t draw”?

By Glen Nelson

March 20, 2020 - I am in New York City during the COVID-19 epidemic. So far, my family and I are ok. Confined in our small apartment for weeks at a time, I’ve decided to do an experiment. I love art and consider myself to have an artistic personality. Still, I can’t draw. I’m not exaggerating much here—I can barely hold a pencil. I’ve wanted to try to draw for as long as I can remember, but I have always psyched myself out. The last time I made a drawing was in 8th grade art class (it got shut down when some classmates threw bottles of paint out the third story window onto the sidewalk below). I have drawn nothing since then. I don’t even doodle, but I’ve thought about drawing over the years as something I might enjoy as a creative outlet. That impulse hasn’t translated into action, until now. Earlier this year, I asked a good friend who is both an artist and an art teacher what to do. He said—I’m paraphrasing—”Stop being such a baby. Just draw something!” Ok. I’ll try. I purchased a book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, and I’m determined to go through it, using it like a workbook, and document whatever happens here. I apologize in advance. These drawings aren’t gonna be good.

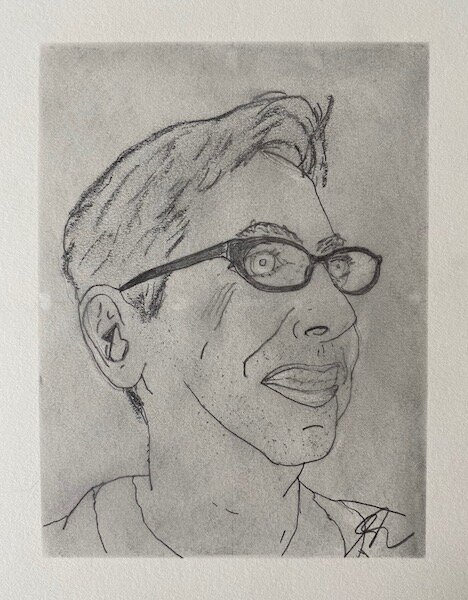

March 21, 2020 - Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain by Betty Edwards was a bestseller that was published when I was in high school. It’s sold nearly 2 million copies, in the U.S. alone. At the time it appeared, neuroscience regarding left brain/right brain distinctions was emerging in popular culture. This book got a lot of people to think of their own minds differently and to take up a pencil and draw. I wasn’t one of them, but I was intrigued enough to want to come back to it 40 years later. There are plenty of how-to books on learning to draw available. I chose this one because the publisher also sells a kit with drawing supplies, workbook, and tools. I needed those. My plan is to read the book, proceed through the exercises, and journal about what comes of it. I’m nervous and embarrassed in advance. One of my first assignments is to make a self-portrait. Here it is.

I know my insecurities well enough to say that my first impulse will be to make a joke of this drawing, to tell you how bad it is before you can tell me how bad it is. (Is this the kind of pressure that artists feel whenever they pick up a paintbrush or a pencil?) But I’m going to resist that reaction of skittishness throughout this journaling exercise. I’m not going to allow myself to be harsh regarding these drawings.

I can report that my emotional reaction to the self-portrait is a slight sense of accomplishment. It’s not exactly pride but a tentative sense of relief. It took a while to draw it. I’m an impatient person, and that’s something I’m just going to have to get over if I want to develop drawing skills. Maybe most troubling, I realize that I don’t look very closely at things. I’m a skimmer. The book talks a lot about careful looking. That’s hard for me. I’ve never been diagnosed with a learning disability, but other members of my family have, and I suspect that I have learning deficits, too. I’m realizing immediately that to draw, I need to slow it down and get the parts of my brain involved that can measure the distances between one thing and another thing and then capture that on the page.

March 22, 2020

To prove the point about left brain/right brain theory, the book has me look at a drawing that Picasso made of Igor Stravinsky and copy it. I’m a fan of both Picasso and Stravinsky. Here’s a little tangent that’s not in the book: Picasso made this drawing in 1920 for Stravinsky in Rome and gave it to him as a gift. Stravinsky packed it in his luggage, but as he crossed the border, the military authorities found it in his luggage and wouldn’t let him keep it. They didn’t believe it was a portrait. Stravinsky tried to explain and tell them it was actually made by a distinguished artist, but no go. They said, “It is not a portrait, but a plan.” They thought he was a spy. Anyway, they wouldn’t let him pass through with the drawing. He was held at the border for a while. Finally, Stravinsky had to send the drawing to the British Ambassador in Rome who forwarded it to Paris in a diplomat’s pouch.

Back to my assignment, I made the drawing by looking at the Picasso upside down. That’s the theory that the author wanted me to explore. It has to do with right brain engagement when the stimuli aren’t easily “read.” So instead of looking at Stravinsky’s hands or pants or chin, I’m simply looking at a sloping line, a curved line, an edge relatively close or far from another one. When I turn my drawing right side up, here’s what I have.

I feel encouraged by this, although I ran out of room on the page and cut off most of poor Igor’s head. It didn’t really take very much time to make, either, about 30 minutes.

It’s silly, probably, but I’m starting to think of drawings I’d like to make in the future. I like to grow things, and I’d love to learn how to do botanical drawings of my vegetables and flowers. I have some favorite artists who created “simple” line drawings—Ellsworth Kelly and Henri Matisse are two—and I think it would be great to see if I could do something like they did. These are projects far too ambitious for my current skills, yet I find myself imagining finished drawings I someday will have made. I don’t imagine feeling a need to show them to anybody, just for myself, that’s all I’m thinking about. When I look at things around me, I say, “That composition would make an interesting drawing. I could probably do that.” It’s kind of crazy, right? I’m not so deluded to think that any of these drawings will be what I would normally consider good if anybody else made them, but for me, they’re good.

March 23, 2020

I’m not including every drawing assignment from the book here. I’ve also made a drawing of a memory. I chose the subject of my daughter as a child in Central Park. It looks like a toddler made it. I did one drawing just staring at my hand. There was another one of me looking at the lines in my palm and not looking at the drawing at all until the timer was up. It’s sort of a cool, abstracted thing. Today, I made a drawing of my left hand holding a pencil. Here it is.

This is a really interesting experience for me. I have this illogical bias about creative artists and how differently they’re wired. I wrongly presume that talented people can just sit down and do amazing things without sweat—pianists can sit down and sight read any piece of music, artists can pick up a pencil and freehand beautiful images, authors can write out a story from start to finish without revisions. Yes, I know that’s bogus. I have concert pianist friends who tell me how they wrestle notating their fingerings for every composition they perform in concert. I’m an author myself and know that I rewrite things again and again, that I use a thesaurus all the time to find better words to use, and so on.

The tools I used to make this drawing were mostly new to me. My kit came with a little, clear plastic square with a simple four-panel grid on it. I rested the plastic over my left hand, and with a wet erase marker, I traced an outline of my hand on the plastic. That was an ah-ha moment for me. It reminded me of a documentary I watched last year, Tim’s Vermeer, about a curious non-artist named Tim Jenison who figures out the optical devices that were used by Renaissance master painters, and he makes his own copy—and it’s a very, very good one—of a gorgeous Vermeer painting, The Music Lesson. Tim isn’t an artist at all.

For my hand drawing, I took out a piece of paper and marked the same dimensions with the same grid on it as is on my plastic square. Before I started to draw on the paper, I took a piece of masking tape and created a little mat around the edges. I had a small stick of graphite that looked like a piece of charcoal, and I filled in the space. Then I took a little piece of toilet paper—something of a rarity in our household right now—and smeared it all together to make a gray background. I felt like a real artist doing that. Quadrant by quadrant, I drew the same outlines on the paper that I had traced on the plastic. And as I made little mistakes and had to erase, I just picked up the toilet paper and rubbed it around until what I had erased was gray again and could be drawn over. When I was done, I had a question for myself, “Did I just make that?!”

March 24, 2020

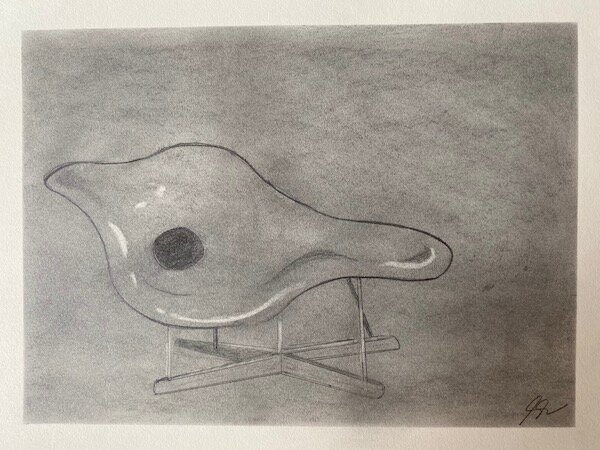

Encouraged by yesterday’s drawing, I am eager to start on the next project which is to draw a chair. The point of the lesson is to get better at noticing negative space—the “empty” areas around the objects we see. My apartment has lots of good chairs. Collecting them is a hobby of mine. I chose something pretty challenging, the Eames “La Chaise,” designed in 1948 for the International Competition for Low Cost Future held at the Museum of Modern Art.

Funny story: The “low cost” part was wishful thinking. The chaise was never put into production while Charles and Ray Eames were alive because nobody could figure out how to manufacture it at anything nearing a reasonable price. In 1991, a Swiss furniture manufacturer, Vitra, joined with the Eames estate to produce it in fiberglass and oak, at last. We convinced Vitra to sell one to us at the equivalent of an architect’s discount—yes, that was a bit of a stretch of logic—and when it arrived, the manufacturer said that we were the only people in America outside of museums to have one. They asked if we would allow people to rent the chair for photoshoots and such. Long story short: That chair paid for itself.

Over the years my kids have crawled through its hole and slid down it like playground equipment. My wife practically lived in it when she was pregnant. It conforms to her body perfectly. We have a long history with it. The object means something special to me.

Back to the drawing. I don’t know how to shade drawings or show contour. The book doesn’t really try to teach techniques like that, either. It says to observe and capture what you see. I chose this subject for the drawing because it would force me to figure out some of those things by trial and error. The chair is nothing but curved, contoured lines. Here’s what I drew.

I used the same process as the last drawing with the plastic grid, but since I was looking at the chair from across the room, it was slightly harder to do that. I put my eraser to work a lot. Normally, I would have quit after trying and failing for a while. With this one, though, I had the outline that I traced on plastic, and all I had to do was look and transfer to the drawing the form, shadows, and reflections of light that I observed directly.

I’m especially happy how the base of the chair turned out. I can’t draw a straight line for the life of me. I was getting frustrated, then I thought, “Can’t I just get a ruler and do it?” Why did I think it’s cheating to use a drafting tool to make a drawing? Isn’t that “drawing,” too?

March 25, 2020

Today’s lesson was hard for me, and it took a couple of hours to complete it because it’s so different from anything I’ve tried to do before. It’s all about perspective and proportion. I don’t know how to do any of that. I hazily remember in 8th grade the teacher had us draw a house with a sidewalk in the front, and all of the lines of the roof, windows and doors had to go to some distant vanishing point. The book doesn’t go into techniques like that. Instead the author encourages you to observe closely the angles of things and measure them in a way that I thought was goofy, but actually works: You hold the pencil in your hand with your arm extended and pointing toward what you’re trying to “measure.” With one eye closed, you basically move your thumb on the pencil to mark the distance from the eraser to wherever the thumb is. First you find some baseline length. For me, it was the width of the chest of drawers. That is basic unit of measurement. The rest of the lines are ratios of that.

There’s a handy little tool in the kit that helps with angles—two thin plastic strips with a marked line down the middle hinged together with a grommet. It has “angle finder” printed on it. You can fan those out and then mark the angle on the drawing. The assignment was to draw some interior that has lots of angles. Self-quarantined in my apartment, this is the perfect assignment. Here’s my drawing.

This is my first big drawing. The paper size is 14 x 11 inches. I didn’t get everything just right. From the start I knew that I wanted it to be really clean—just lines with no shading—but I learned how my mind can play tricks on me. I know, for example, that the furniture is square, but if I draw it square that doesn’t account for my vantage point and the distorting tilt of perspective. So the more I measured with my handy dandy angle tool, the more “real” things looked. I’m especially happy with the wooden chair in the foreground. It was really tough to figure it out.

I felt a lot of pressure to do it justice. The chair was made by one of my art icons, Donald Judd. Though not particularly comfortable, we love that chair. My wife used to teach high school, and one of her first students was Judd’s daughter, Rainer. I know, that’s an insignificant, six-degrees-of-separation thing, but it’s a connection to greatness that makes me smile whenever I think about it.

In the drawing on the cabinet, there’s a little cactus, an orchid that I have little hope is going to bloom again, a sculpture, and a photograph of Marcia and me. The bigger painting is by Peter Everett. No, I didn’t really try to copy it closely. Making real art is too hard.

March 30, 2020

I’ve known that another portrait drawing was an upcoming assignment, and I’ve been dreading it. The book warned me about these self-doubts and advised me to push through them. I found some aspects of the process pretty easy: general shapes and lines. I have no idea how to capture eyes and mouths, though. The book had great suggestions, but still I can’t quite see how I went wrong. The finished drawing looks to me like a cross between the husband in the animated movie 101 Dalmatians and Dustin Hoffman in Tootsie. Here it is.

And yet, when I look back at the first self-portrait I made just a week or so ago in comparison, I know I’ve come a very long way. I need to feel motivated and pleased by that. At any rate, I’ve tried my best to tackle these projects with determination.

I will say that these exercises, and especially this self-portrait, make me want to park myself down at a museum and take a very close look at Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velasquez, Hals, and Holbein. To get verisimilitude is one thing—I’ll probably never be close to that effect, frankly—but how do these great artists capture the inner life of their human subjects? Art is a miracle. I wish more people tried to draw. They would walk away from the experience with an entirely different kind of appreciation, at least that what’s happening with me.

April 2, 2020

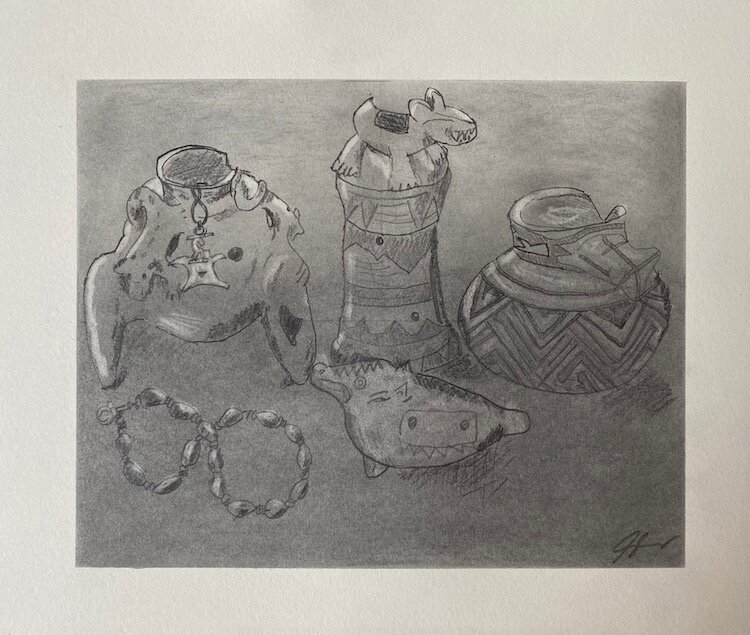

Today I have my final project from the book Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain. I’ve been working on shading and cross-hatching, so I decided to try to do a still life drawing with more emphasis on light and shadow. First, I had to create a little tableau.

When I was a missionary serving in Costa Rica, there was one month when the exchange rate went berserk. The amount of money I normally spent for a Big Mac was enough to buy ten of them. So, off I went to the art gallery in San José—you know, like all missionaries would do. I ended up with some beautiful Pre-Columbian art. For the drawing today, I staged four ceramic objects—the one on the far right is Southwestern Puebloan. There’s a gold bird that’s on a chord, and a carved shelled necklace that my missionary companion at the time, Lesmes Morales, made for me. He is from a tribe from Guna Yala off the coast of Panama. Here it is.

I’ve come to the end of the book, and I’m a bit sad to be ending my little experiment, at least as far as its journaling goes, but I don’t intend to stop drawing. This has been transformational for me. At the end of the book, Betty Edwards says this about one’s progress from their first drawing exercise to the last one, “A friend might remark upon looking at your drawing that you had uncovered a hidden talent. In a way, I believe this is true, although I am convinced that this talent is not confined to a few, but instead is as widespread as, say, talent for reading.”[1]

That’s an interesting thought. What if drawing really is as natural as reading, speaking, or walking?

What’s next for me? I respond to conceptual art, and I’m wondering how I can merge my love of literature, dance, and music with drawing. Is there a way I can use color theory to map out the structure and effects of a poem, for example? Can I take the movement of choreography and turn it into a graphic line, my own labanotation? Can I formulate some kind of system to visualize music as color, maybe related to synesthesia? What will I make?

New York, April 2, 2020

Now, what will you make?

[1] Betty Edwards, Drawing on the Right Side of the Brain, Jeremy P. Tarcher/Putnam, 1979, 1989, 1999, p. 224.